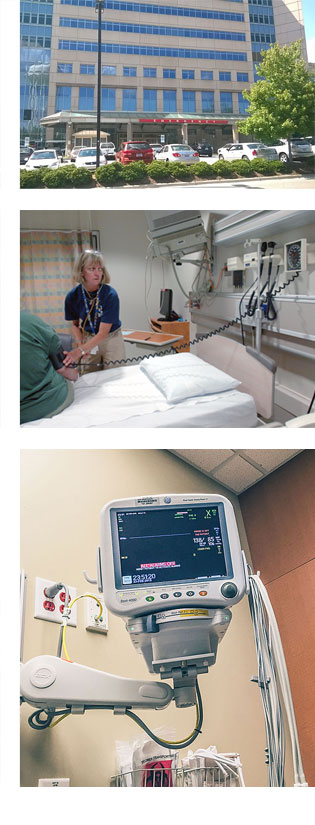

By definition, a visit to the local emergency room is an emergency. I recently spent two days incarcerated in an observation bed in our local emergency room. An asthma flare led us to the hospital four miles away. With my chest pain, age, and family history, I got the special welcome reserved for potential heart attack patients.

By definition, a visit to the local emergency room is an emergency. I recently spent two days incarcerated in an observation bed in our local emergency room. An asthma flare led us to the hospital four miles away. With my chest pain, age, and family history, I got the special welcome reserved for potential heart attack patients.

Though it may sound counterintuitive to plan in a crisis, one can certainly plan for a crisis. Understanding what will happen on a visit may help you anticipate what’s ahead. You are probably going to use an emergency department at least once if you are over 65. ERs rule out acute and life-threatening conditions; they are not a substitute for your doctor’s office.

The Canadian Geriatrics Journal (December 2014) studied more than 34,000 seniors and discovered the obvious:

- Seniors are more often acutely ill when presenting to an ER than their younger counterparts.

- Common reasons for seniors to visit include heart disease and failure, stroke, other cardiac issues, pneumonia, abdominal, kidney and bladder disorders, and fall-related injuries.

- Canadian seniors have a higher ER utilization than their countrymen under 65.

- And more than half of ER visitors left without a definitive diagnosis.

By day, I’m a hospital administrator. In theory, I should understand the process. My weekend visit reminded me of things I can do to get the most out of the ER.

- Prepare for your visit years in advance. Am I facetious? No. Some seniors unwisely use a hospital ER visit as a point-of-entry to services. Chances are your doctor is linked to the hospital’s electronic medical records system. My ER minders had immediate access to my records and doctor’s visits because I regularly visit my medical practitioner.

- Have an advance directive, and always have a copy with you. An advance directive is a legal document that spells out your wishes for health care if you are incapacitated. Family

members need one. It’s a good idea to have one in your records at your doctor’s office. However, keeping one with you is the best idea. Sometimes surprising things happen. A relative of mine, brain dead after a car accident, was kept on a ventilator against her stated wishes. She did not have her directive with her at the time of the accident. (You can download a copy of your state’s advance directive at http://www.caringinfo.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3289). - Be familiar with your history. Everyone who enters an emergency department gets triaged. The word triage comes from the French and means “to separate out.” In an emergency situation, all incoming patients are prioritized by their level of urgency. Your chest pains may trump the broken ankle ahead of you. Get to the heart of the matter so that you can help the ER staff help you. Being familiar with your medication also helps. While it may be on the electronic medical record from your doctor’s office, you will need to know when you took your last dose.

- Grab a bag from home if you can on the chance you are admitted. I was in “23-hour observation.” I had several heart tests that required a blood draw every few hours. Luckily, I threw a few things in a bag, including my medicines in original bottles (in case they needed to verify), my cell phone and charger, my health insurance card and ID, and slipper socks for my cold feet. What I did not think about was bringing a book or my tablet for the boredom between tests. Having the phone is critical to call relatives.

- Advocate for yourself. My heart was fine, but I went for my asthma. After getting a clean bill of health from the various heart tests, I had to ask the ER doctor about my asthma. I was still wheezing, and my oxygen level was low, and my blood pressure was high. No one will advocate for me like me. Ask any questions you have when the doctors see you at discharge; make sure you understand your discharge orders and follow-up.

Hospitals are multi-layered, complex, busy institutions. Most caregivers went into medicine with a passion for healing. That doesn’t absolve us of our responsibility to manage our care, even in a crisis. A bit of forethought before there is an emergency may be a lifesaver.

Find my books and columns at www.amyabbottwrites.com.